The Flood: From Catastrophe Myth to Human Responsibility

What if the Flood were not about an ancient cataclysm, but about us? Long before modern science, the biblical narrative articulated a disturbing intuition: a world can collapse without divine wrath or natural accident, simply because humanity persists in its choices. To reread the Flood today is to question our relationship to knowledge, to collective responsibility, and to a form of destruction that no one decides alone, yet that everyone makes possible.

Introduction — When Ancient Narratives Speak to the Present

The Flood is often read as an ancient fable, one religious myth among others, or as a primitive attempt to explain a natural disaster. Yet a closer reading reveals something else entirely. The story is not primarily concerned with the end of a world, but with the cause of that end. And that cause is neither cosmic nor accidental: it is human.

Through its biblical reworking of a much older mythological theme, the Flood becomes one of the earliest narratives in which humanity is held collectively responsible for the destruction of its own world. In this sense, it resonates uncannily with our present moment.

From the Flood to Enoch: Fault as the Transgression of Knowledge

The Flood narrative does not stand alone within ancient biblical tradition. It is preceded—especially in parallel and more radical literature—by the story of Enoch and the Watchers.

In this framework, the corruption of the world is not merely moral or violent; it is cognitive. The Watchers transmit forms of knowledge to humanity that exceed proper measure—techniques, weapons, domination over nature, mastery of life itself—without humanity being capable of assuming the consequences.

The fault, then, is no longer only a matter of acting wrongly, but of knowing without discernment, of wielding powers without a corresponding ethical maturity. The world becomes disordered because humanity gains access to levels of control that surpass its moral capacity.

This logic is profoundly modern. It anticipates a humanity that does not destroy out of ignorance, but through the unreflective use of knowledge that is nonetheless correct.

The Flood as a Matrix of Our Ecological Crisis

What the biblical Flood describes corresponds, with troubling precision, to our contemporary crises.

There is no supernatural punishment today, no celestial anger, no sudden cataclysm. Instead, there are:

- locally rational decisions,

- individually understandable economic interests,

- a global destruction that no one explicitly desires, yet that everyone produces.

The extinction of species, climate disruption, the exhaustion of soils and oceans all follow this same logic: a diffuse, cumulative responsibility without a single identifiable culprit. One can recognize here strikingly modern situations: the atomic bomb, whose destructive use no individual scientist intended; genomic knowledge, which promises healing while also carrying eugenic risks; unrestrained mineral extraction, indispensable to our technologies yet devastating on a planetary scale; mass extinctions and pervasive pollution, the aggregated outcome of ordinary choices; and artificial intelligence, born of local innovations whose global effects escape their creators.

The Flood narrative anticipates this type of catastrophe. It shows that a world can collapse without any individual explicitly willing it. It is enough for mechanisms of violence, exploitation, and indifference to become systemic.

This is where the parallel with the modern notion of a crime without a single perpetrator becomes unavoidable. Everyone participates; no one decides alone. The catastrophe is not the result of an act, but of a system. Responsibility is real, yet diluted, fragmented, and rendered almost intangible—and therefore politically and morally comfortable.

The Ark Is Not a Technological Miracle

One point is often overlooked: the ark is not presented as a technical feat.

It does not save the world. It preserves a trace of it.

It is limited, enclosed, fragile. It does not dominate the elements; it submits to them. It symbolizes another way of inhabiting the world: preserving rather than conquering, transmitting rather than exploiting. In this sense, the ark functions like a seed held in reserve—a fragment of life withdrawn from destruction in order to allow for a later, discreet, patient rebirth, rather than a spectacular reboot of the world.

Read this way, the ark is not a fantasy of omnipotence, but a model of restraint. It does not avert catastrophe; it limits the losses.

Here again, the resonance with our time is direct. Humanity now projects itself beyond Earth itself: toward the Moon, Mars, other stellar systems. It imagines travel at the speed of light, the folding of space-time, even cosmic shortcuts. This technological flight forward sometimes resembles an ark displaced into the sky—not to preserve the world, but to imagine its replacement, or perhaps its replication.

Conclusion — A Myth That Leaves Us No Alibi

The biblical Flood does not tell the story of the end of the world. It tells the story of the end of innocence.

It affirms that humanity can destroy its own habitat, and that no god will necessarily intervene to prevent it. The world is entrusted, not guaranteed.

This ancient narrative does not accuse us; it warns us. And that may be precisely what makes it so uncomfortable today.

We are no longer in a state of mythic ignorance.

We know.

And that is exactly what the Flood was already asking us to assume.

For the true warning of the Flood is not that the world can disappear, but that those who destroy it may continue to believe themselves innocent until the very end.

Alexandre Vialle

Author’s Note — Why Revisit These Narratives Today

This text does not seek to resolve a theological question, nor to offer a confessional reading of the Flood. It is grounded in a critical, anthropological, and symbolic approach, attentive to what ancient narratives say about humanity more than about God.

My starting point is simple: some myths endure across centuries not because they explain the world, but because they give form to fundamental human responsibilities. The Flood, as reread within the biblical tradition, belongs to this rare category of narratives that shift the question of disaster away from natural fatality and toward collective human action.

By linking the Flood to the traditions of Enoch and the Watchers, and then to our contemporary crises, I have not sought an easy analogy, but a continuity of structure: that of a humanity capable of producing effects that exceed it—through violence, through knowledge, or through the very organization of its systems.

This essay is therefore an invitation to reread these narratives not as relics of the past, but as demanding mirrors. Not to seek ready-made answers, but to recognize a question that remains open: what are we doing with the world entrusted to us, when nothing can any longer be attributed to the gods, to chance, or to ignorance?

You may also like

- Maurice Ravel, Une barque sur l'océan (A Boat on the Ocean) Miroirs n° 3, M. 43, by Bruce Liu on YouTube:

- Alexander Scriabin, Piano Sonata n° 10, Op. 70 (1913), by Mikhail Pletnev Link to Spotify

- Claude Debussy, La cathédrale engloutie (The Sunken Cathedral), by Daniel Barenboim Link to Spotify

- Another article of mine The Watchers: What the Bible Leaves Unsaid About Noah and the Giants

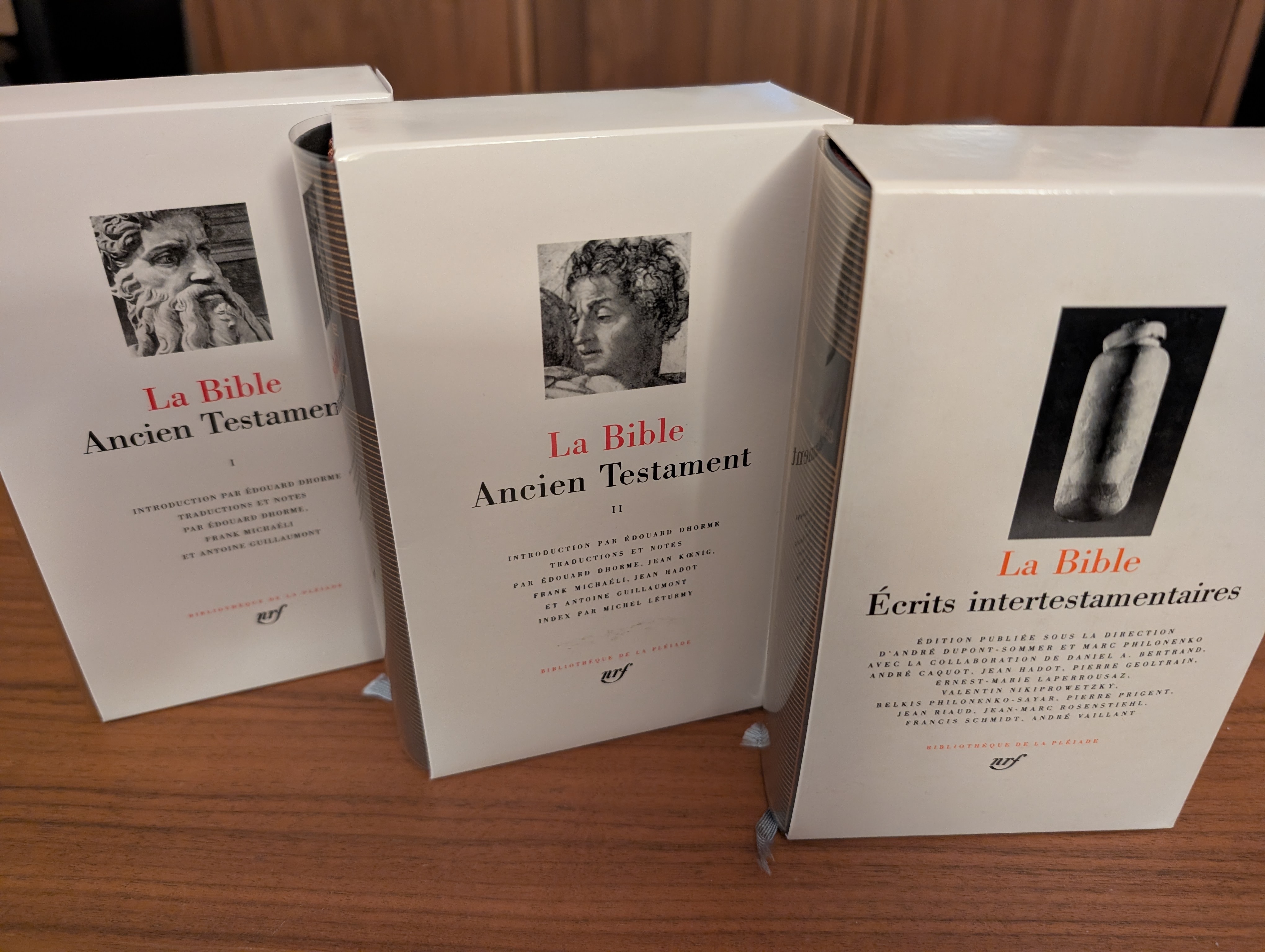

- La Bible. Ancien Testament, tome I. Trad. de l'hébreu par Édouard Dhorme, Antoine Guillaumont et Frank Michaéli. Collection Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (no120) ISBN: 9782070100071. Éditions Gallimard.

- La Bible. Ancien Testament, tome II. Trad. de l'hébreu par Édouard Dhorme, Antoine Guillaumont, Jean Hadot, Jean Koenig et Frank Michaéli. Collection Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (no139) ISBN: 9782070100088. Éditions Gallimard.

- La Bible. Écrits intertestamentaires (avec le Livre d'Hénoch). Trad. de différentes langues par Daniel A. Bertrand, André Caquot, André Dupont-Sommer, Pierre Geoltrain, Jean Hadot, Ernest-Marie Laperrousaz, Valentin Nikiprowetzky, Marc Philonenko, Belkis Philonenko-Sayar, Pierre Prigent, Jean Riaud, Jean-Marc Rosensthiel, Francis Schmidt et André Vaillant. Édition publiée sous la direction d'André Dupont-Sommer et Marc Philonenko. Textes présentés et annotés par les éditeurs et les traducteurs. Collection Bibliothèque de la Pléiade (no337) ISBN: 9782070111169. Éditions Gallimard.